Aretha Franklin’s “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” surely wasn’t a love song directed at the Queen of Soul’s mother, but a close reading of Nancy Chodorow’s “The Sexual Sociology of Adult Lifefrom The Reproduction of Mothering” explicitly states that a girl owes her entire personal identification to the woman who bore her. Chodorow writes how femininity is essentially innate, while masculinity is much more often adapted than learned first hand from fathers.

Aretha Franklin’s “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” surely wasn’t a love song directed at the Queen of Soul’s mother, but a close reading of Nancy Chodorow’s “The Sexual Sociology of Adult Lifefrom The Reproduction of Mothering” explicitly states that a girl owes her entire personal identification to the woman who bore her. Chodorow writes how femininity is essentially innate, while masculinity is much more often adapted than learned first hand from fathers.

On one hand, this stark developmental difference does not seem like it can be true. After all, “much of a girl’s and boy’s socialization is the same, and…both go to school and can participate in adulthood in the labor force and other nonfamilial institutions.” However, if a qualifier like that meant anything, all children would grow up free from gender roles, and anyone living in modern society can attest that this could not be further from the truth. Chodorow explains that with a woman as a primary caretaker, girls “can begin to identify more directly and immediately with their mothers and their mothers’ familial roles than can boys with their fathers and men.” (265) Logically, this makes sense; why wouldn’t a boy have a harder time developing when his primary masculine role model works 40 hours a week? What makes this realization more interesting, however, is the fact that Chodorow is positing femininity as the default, and masculinity the deviation from the default, calling child development an irony of biblical proportions.

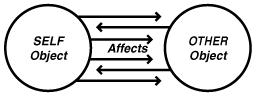

It does beg the question: how can masculinity be the concept to which all aspire when men cannot even call themselves its innate possessor? It would appear as if boys would be as consigned to identifying with the traits of his mother as his sister is. For Chodorow a girl’s development is indeed rather simple: “a girl’s mother is present in a way that a boy’s father, and other adult men, are not. A girl, then, can develop a personal identification with her mother.” (266) A personal identification “consists in diffuse identification with someone else’s general personality, behavioral traits, values and attitudes,” and with a constant feminine role model, a girl can whole-heartedly identify herself with her caretaker and take on all that her mother is as she continues to develop.

For boys, the situation is less concise. With a comparatively more absent masculine role model, the boy engages in positional identification, which, “consists, by contrasts, in identification with specific aspects of another’s role and does not necessarily lead to the internalization of values or attitudes of the person identified with.” Per Slater and Winch, personal identification for a boy is nearly impossible in the absence of a consistent male role model. If masculinity does not depend on a caretaker to imbue itself into a male child, how does it continue to perpetuate itself?

The answer could not have been more obvious, but in a roundabout way, Chodorow looks to the media: “boys…develop a sense of what it is to be masculine through identification with cultural images of masculinity and men chosen as masculine role models. Boys are taught to be masculine more consciously than girls are taught to be feminine.” (266) Surely a girl would engage in the same positional identification in a mother-absent home, but more often than not she has a mother, to quote Glinda from Wicked, “as so many do,” and this gender development grid does a great deal to illustrate how the vast majority of children are brought up from birth.

When explained in that matter, it is harder to question why it is so difficult for women to break from their gender role. Femininity is ingrained, the concept of a wife/mother are instilled in girls from birth involuntarily and unconsciously. At the same time, one can argue that it is equally difficult to transcend the masculine gender role, one that would seem to be less stringent in its development. Chodorow answers that question as ominously as she does questions aimed at girls: “boys appropriate those specific components of the masculinity of their father that they fear will be otherwise used against them…” Like Rubin and Lévi-Strauss before her, Chodorow addresses what anyone in the gender or sexual minority could tell you: the yolk of the gender role is hard to ignore and even harder to bear, regardless of whether one is male or female.

A few weeks ago I discussed Cixous’ “Laugh of the Medusa,” in which the writer explains that society defines woman by their lack of a phallus. Woman is defined in the negative, by what she’s doesn’t have. In reading the excerpt from the Chodorow piece, it became obvious to me that there is a pattern or a rule of negative that governs gender role learning. Although Cixous’ man has a phallus, Chodorow’s mother-reared boys define men by all of the feminine characteristics that the idealized man lacks. This negative conditioning of Chodorow’s boys is just a damaging as the negative definition of women, and not just because it is these boys that grow up to become men who are proponents of oppressive relationships with women.

A few weeks ago I discussed Cixous’ “Laugh of the Medusa,” in which the writer explains that society defines woman by their lack of a phallus. Woman is defined in the negative, by what she’s doesn’t have. In reading the excerpt from the Chodorow piece, it became obvious to me that there is a pattern or a rule of negative that governs gender role learning. Although Cixous’ man has a phallus, Chodorow’s mother-reared boys define men by all of the feminine characteristics that the idealized man lacks. This negative conditioning of Chodorow’s boys is just a damaging as the negative definition of women, and not just because it is these boys that grow up to become men who are proponents of oppressive relationships with women.